America’s food culture reflects the people who arrived on its shores and made a contribution to its many culinary traditions. The food traditions of enslaved African Americans have had a profound and lasting influence on America’s culinary heritage. Centuries later, that impact is finally garnering the attention it so deserves thanks to a book and a Netflix documentary called High on the Hog.

Brown stew chicken over cilantro-coconut rice consists of grilled chicken thighs with red pepper and delivers the aroma of a Saturday morning church barbecue. Like the chicken, the rice is tender, juicy and savory.

West African ginger-pineapple juice is loaded with cinnamon upfront, followed by sweet pineapple in the middle and a tangy ginger finish that continues well after your last sip. It’s anything but shy due to its bold, bright and refreshing flavors.

The History of Juneteenth

On January 1, 1863, during the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln declared freedom for all enslaved people through an Executive Order known as the Emancipation Proclamation. While many of us were taught this act immediately ended slavery, the reality was quite different.

It took more than two years after President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was issued for Union soldiers to deliver notice to the last Confederate state – Texas – that slavery had been abolished and the war, which ended on May 9, 1865, was over. On June 19, 1865, General Order Number 3 was read in Galveston, Texas, by General Gordon Granger. It stated: “The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired laborer.”

West African peanut-butter soup bestows an aroma that begs to be experienced. Sweet and savory, creamy and a little salty, it’s loaded with chunks of carrots, onion and spices that deliver robust flavor.

While we as a nation celebrate Independence Day on July 4th, Juneteenth festivities are rooted in the event that took place in Galveston on June 19. Juneteenth celebrates the emancipation of enslaved people – of our fellow Americans who were left behind – after the final Confederate States recognized the end of slavery. In 1980, the Texas legislature established Juneteenth as a holiday, known as Emancipation Day in Texas. The holiday is often celebrated with lots of food, outdoor barbecues, gatherings with family and friends, church services and reflection. Other states and jurisdictions have since followed suit. On June 19, 2019, Gov. Tom Wolf signed legislation (HB 619) that designates the date as Juneteenth National Freedom Day in Pennsylvania. In 2021, Juneteenth was declared a holiday in Lancaster County (beginning in 2022), and also became the newest federal holiday – Juneteenth National Independence Day – since Martin Luther King Jr. Day was added to the calendar in 1983.

What happened in Galveston, Texas, on June 19 wasn’t so much a finish line as it was a milestone for the African American community. Ending slavery was no guarantor of liberty and certainly not of equality. Juneteenth did not atone for centuries of unpaid labor and brutal suffering. “Free-ish” has been used to describe what Juneteenth brought forward into the Jim Crow era, the start of an on-going, generations-long climb towards equality.

On that centuries-long journey, the food that came along with it became an important part of this country’s food history.

The African Diaspora – The Journey of Food

Because of the African diaspora – bringing seeds, recipes, expertise and skilled labor from Western Africa to the Americas – American cuisine was profoundly influenced by enslaved people.

High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America, a New York Times best seller by Dr. Jessica B. Harris, led to the Netflix documentary series that shares the same name. Harris explores the African diaspora, the journey of food from Africa to the Americas and the Caribbean. She details how cooking traditions and cultivating expertise arrived in what is now the United States through the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Cream of turkey soup is akin to chicken pot pie that is enlivened by African spices. Hearty and savory with delightful textures, it consists of shredded turkey and a creamy base, carrots, peas and corn. There are no misses here.

I’m sure you’ve heard the term “living high on the hog” and perhaps questioned its meaning. The phrase has a literal connection to hogs and was originally a food term that relates to the fact that the best meat from a hog is said to come from its back and upper legs. In the ninth century, when the phrase first originated, it pertained to anyone who could afford to eat the “high parts” of the hog while those less fortunate were afforded pork belly and other “lowly” parts. That practice certainly applied in the case of plantation owners and the people they enslaved. The fact that the enslaved people got “creative” with their meager portions and provided us with the makings for barbecued ribs and other dishes is now part of food history.

In the Netflix series, Harris remarks, “Through food, we can find out that there is more that connects us than that separates us. What we eat and what we discover brings us together. It’s a communal table. It’s how we know who we are, and it’s how we know we’re connected.” For example, Harris shares that starches such as rice, cereal and yams (not to be confused with sweet potatoes) were cooked throughout all of Africa with stews for sopping up the rich flavors of meat, vegetables and sauces.

Chef Oliver Saye

In February, the Dorothy Height Social Justice Club at the YWCA Lancaster hosted an online event that expanded on the Netflix series, High on the Hog, which was suggested viewing before the conversation featuring Lancaster chefs, with their cooking available for advance pickup.

Chef Oliver Saye shares his personal culinary heritage, as well as that of West Africa, with Lancaster through his food truck, catering service and teaching appearances. Photo courtesy of Oliver Saye.

Among the speakers was chef Oliver Saye, owner of homage: Cuisines of the West African Diaspora. He also works at the Boys & Girls Club and is deeply passionate about sharing West African history through food. Perhaps un-ironically, chef Saye is a distant cousin to Michael W. Twitty, a James Beard Award-winning author and culinary historian who is featured in the High on the Hog series.

Chef Saye has graciously shared several lengthy conversations about his history and the rich history of his dynamic cooking. “Every food in the [African] diaspora is us,” he relates.

Born in Liberia, he grew up in Lancaster after coming to the United States when he was 5 years old. His maternal ancestry is native Liberian, while his father’s is Guinean. As such, chef Saye shares a deep connection to the people who were taken from West Africa through the Transatlantic Slave Trade. He also maintains a deep connection to their food. “There’s this dish in West Africa called Jollof. It’s red rice,” he explains, noting that in America, red rice came to be known by various names. “We get the same kind of rice in different locations,” he points out. “In the Carolinas, it’s called red rice. In Louisiana, it’s jambalaya.”

“When our ancestors came here, whatever country they came from, they made that [country’s food]. That’s us,” chef Saye states. “That had a foundation from West Africa. Yuca in the Caribbean is cassava in West Africa. In the American South, it’s sweet potato pie. That’s us. There are all these linkages and it happens for a reason. When they came here, they were trying to cook what they were familiar with.” Hence, American cuisine is rooted in history, and a great deal of it is from West Africa.

Chef Oliver Saye (left) and his distant cousin, Michael W. Twitty, whose book, The Cooking Gene, claimed two James Beard awards in 2018, including Book of the Year. In a blog on his website, afroculinaria.com, Twitty writes, “Facing my/our past has been my life’s journey. It’s also been at times devastating and painful. But reflection in no way equals one second in the lives of the enslaved women and men whose blood flows in my veins. I had the privilege of rediscovering my roots on a North Carolina plantation at a dinner we prepared for North Carolinians of all backgrounds. Knowing that the enslaved people who once occupied those cabins could never have dreamed of that rainbow of people sitting together as equals in prayer, food and fellowship while my Asante and Mende roots were being uncovered after centuries of obfuscation was for me a holy moment.” Photo courtesy of Oliver Saye.

“The initial wealth of this country – before it was a country – was rice,” he continues. “It was enslavers that went to West Africa to get people who knew how to cultivate rice. The narrative of the enslaved is that they were ignorant, stupid and unskilled, but they had centuries of cultivating rice. It wasn’t picking people blindly. You could relate that to indigo, tobacco, cotton, all of these other slave trades,” he says. “Eight of the 10 millionaires were from South Carolina, and that was based on rice.”

In Charleston, South Carolina, gold rice dominated the economy for centuries, giving the region the nickname, the “Rice Coast.” African Americans, including the Gullah people, built that economy. However, before and soon after the Civil War, rice was no longer a productive industry. In 1910, the start of the Great Migration further brought that period to a close with the movement of 6 million African Americans from the rural South to northern urban cities. “The perception was that slaves were uneducated or unskilled,” says chef Saye. “You couldn’t build a nation on the backs of unskilled people. We were experts in those fields. We need to carry that.”

How I Learned About Juneteenth

My first encounter with Juneteenth was from a coworker, Tavorice, years ago, when I lived and worked in Louisiana. I can’t recall how the topic of Juneteenth came up; it could have been in a conversation or something shared on social media, but I’m certain it was through Tavorice.

When I moved to Baton Rouge, I quite naively walked into a job situation where I was seen as an outsider. Day-to-day interactions were full of subtle, often unspoken animosities that made work and social interactions difficult. It wasn’t always what people said so much as how they said it, though sometimes it was indeed what was said. Resentment manifested as inaction in challenging situations or in being thrown under the bus, with constant reminders that I didn’t belong.

One night, a manager took me aside in private and said of the staff, “They’re never going to accept you. Do you want to give your two weeks’ notice?” The issue was structural: I didn’t belong and I took someone else’s job by being there. Another coworker later admitted with regret, “I hated you. I did everything I could to make your job hell.”

In the middle of that environment stood Tavorice. He was genuine and kind, offering real perspective and kindness when it wasn’t popular to do so. A young Black man from the South, Tavorice offered encouragement that kept me going, and he likely understood what was happening better than I ever could. My experience wasn’t about race and it doesn’t compare. All I had to do to escape that situation was move back home to Lancaster. Yet that experience was the closest I’ve come to understanding what being labeled and treated as different really means.

Today when I think of Juneteenth, I’m reminded of Tavorice. A sense of gratitude and strength comes to mind. I can’t fathom the complexities and joy Juneteenth brings to the African American community, but I will share in celebrating it.

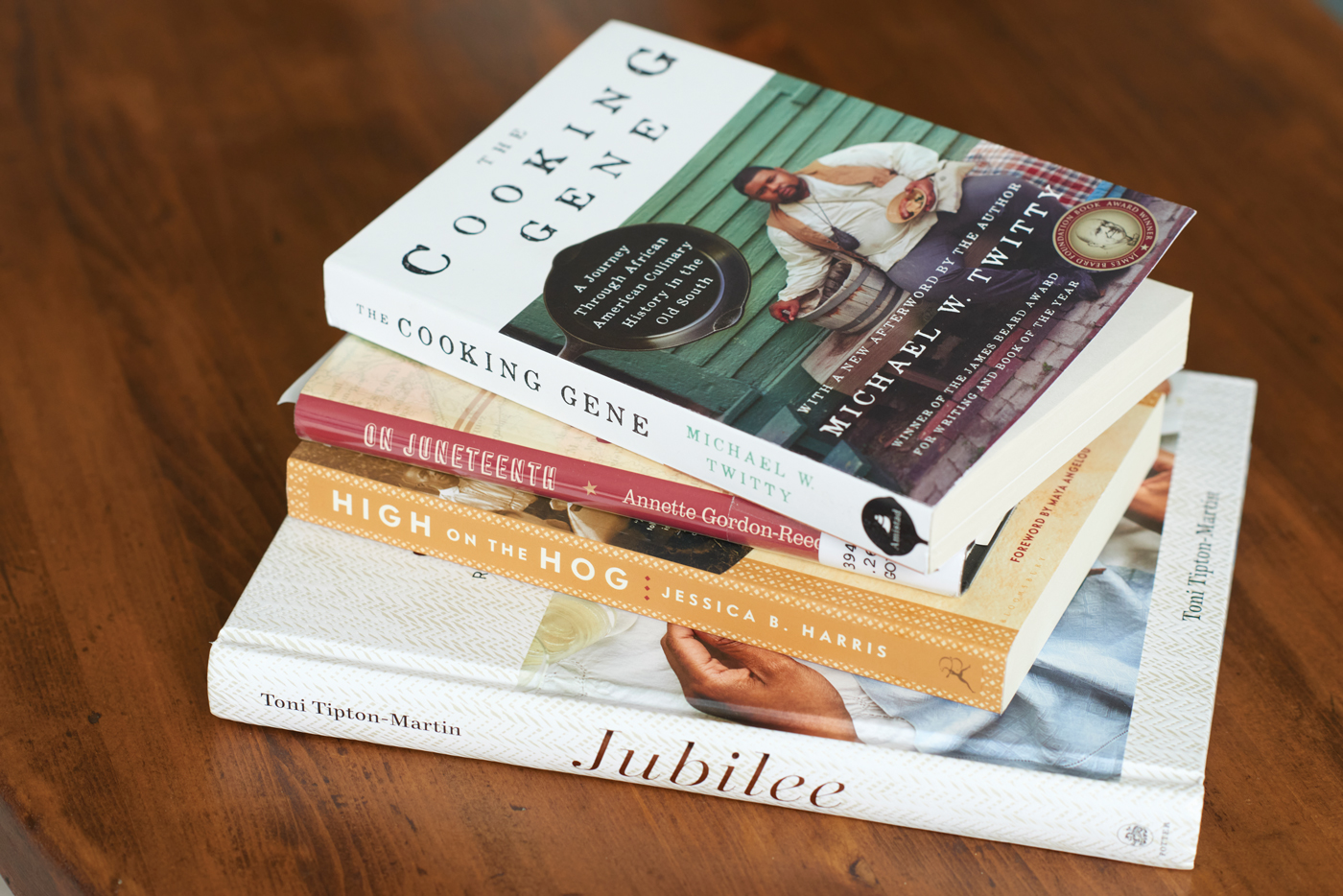

Recommended Reading

The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South by Michael W. Twitty, winner of the James Beard Award for writing and book of the year.

High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America by Dr. Jessica B. Harris.

Jubilee: Recipes From Two Centuries of African American Cooking by Toni Tipton-Martin.

On Juneteenth by Annette Gordon-Reed, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author. Gordon-Reed discusses her life growing up in Texas, her experience as one of the first students to integrate as they relate to African American history, and the echoes of Juneteenth.

Juneteenth in Lancaster

June 17

Zion Hill Cemetery Juneteenth Dinner & Lectures

The event will feature fine West African cuisine from chef Oliver Saye, along with historic lectures and lessons. Columbia Crossing, 41 Walnut St., Columbia. 6-9 p.m. For tickets ($50), call 717-572-7149 or email columbiahistory717@gmail.com. Proceeds benefit the preservation of Zion Hill Cemetery.

June 19

Crispus Attucks Community Center (CACC) Cultural Mixer

The event will feature food, beverages, performances, history and reflection. 407 Howard Ave., Lancaster. 6-9 p.m. Free admission. For more information, visit caplanc.org /juneteenth/.

Local Restaurants, Food Trucks & Caterers to Patronize

Find them all on Facebook

Carolina Soulfrito BBQ Food Truck

Fish Bread & Chicken (FBC) Food Truck

Gourmet Jerk Shack Food Truck and Catering

homage: Cuisines of the West African Diaspora – chef Oliver Saye

Soulfully Famous – chef Lory Thomas

The Big 5 African Cuisine Restaurant, Lancaster

A Concrete Rose (bookstore, micro-winery, café and more slated to open in Lancaster this summer)

Learn

Living the Experience

Lancaster’s historic Bethel AME Church presents a creative, spiritual and interactive reenactment program that takes its inspiration from the role it played in the Underground Railroad. Following the program, visitors share a Southern-style meal. Visit bethelamelancaster.com for details/reservations.

Community Voices

Be sure to visit CAP’s website to view Community Voices, which was filmed in partnership with the Crispus Attucks Community Center and MAKE/FILMS. The video series features African American community leaders, students and others as they read tributes to their role models. Then, those same mentors appear and share the names and memories of those who inspired them. It’s a very touching and well done video series. Don’t miss it. Visit caplanc.org/Juneteenth/.

African American Heritage Walking Tour

First Saturdays through November 5

Volunteer guides lead visitors to 12 significant sites in Downtown Lancaster, some of which relate to the Underground Railroad. Sponsored by the African American Historical Society of South Central Pennsylvania. Visit aahsscpa.org for details.

Race Against Racism Self-Guided Tour

This self-guided tour follows the course that the 2022 Race Against Racism took through Lancaster. This route, developed by the African American Historical Society of Lancaster, Randolph Harris, YWCA Lancaster and Lancaster History, features 18 historically significant points of interest in the city. The tour also features a curated Race Against Racism playlist that allows participants to learn and experience Lancaster City’s history through music and narration provided by local voices. For details, visit ywcalancaster.org/raceagainstracism/course.

SHARE

PRINT